Workplace (or “organisational” or “corporate”) culture has been characterised variously in management literature as:

- Shared values (Peters and Waterman, 1982).

- “The way we do things around here” (Deal and Kennedy 1982).

- Shared perceptions of daily practices (Hofstede et al, 1990).

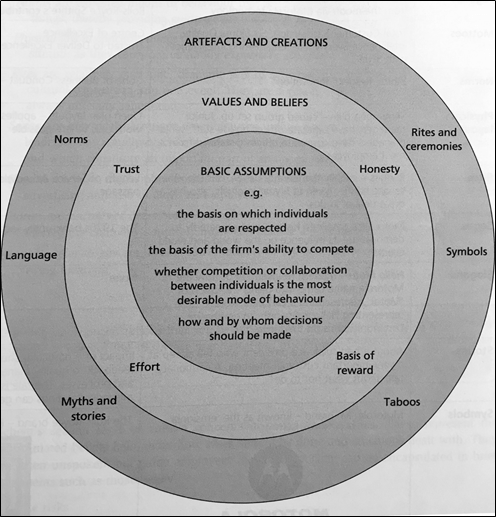

- Basic assumptions, values and surface manifestations (Schein, 2004):

More formally, Schein (1984) has defined organisational culture as:

the pattern of basic assumptions that a given group has invented, discovered, or developed in learning to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, and that have worked well enough to be considered valid, and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems

Schein’s three-layered model of assumptions, values and surface manifestations continues to be influential and used in research (see, for example, Hock et al., 2016). For Schein, culture can be analysed by looking at visible artefacts (for example, constructed environment, architecture, technology, office layout, dress, behaviours or public documents). To understand those surface manifestations, researchers need to look at the organisation’s values. However, values are hard to observe, so it is often necessary to infer them by interviewing key members of organisation or undertaking content analysis of artefacts such as documents and charters. This still represent only the “manifest or espoused values”, so it is also important to delve into the assumptions underlying the interviews or analysis (Schein, 1984)

What determines a firm’s culture?

An organisation’s culture emerges from the values of its founders and early leaders and is passed on through the socialisation of new members (Schein, 1984). Other inputs into an organisation’s culture include “national culture, professional subculture, and the organisation’s own history” (Hofstede, 1981).

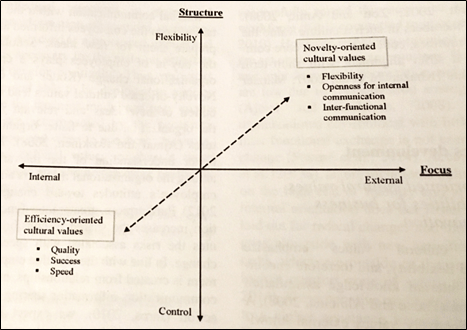

Hock et al (2016) note that there are multiple approaches to conceptualise an organisation’s culture. They adopt a useful model that contrasts novelty-oriented cultural values (emphasising flexible structures and external focus) with efficiency-oriented values (emphasising control structures and internal focus):

These authors found that underlying culture had an influence on the firm’s innovation capabilities, with a novelty-oriented culture found to encourage innovativeness.

Different models for understanding culture underpin tools for use by managers. One proprietary approach is the Great Place To Work® workplace culture assessment, undertaken by Great Place To Work Australia (GPTWA) which measures employee trust and provides gap analysis and benchmarking.

Traditional law firm culture

Certain themes emerge in the literature about law firm workplace culture. The first theme stems from the tension between the practice of law as both a “competitive business practice” and a “noble profession” (Cutler and Daigle, 2002).

Law “as a business” is seen in law firms employing professional managers or marketing personnel, and adopting financially-driven measurements and strategic business plans.

Law “as a profession” includes perceptions that lawyers contribute to society with objectives distinct from a profit motive, a view reflected in professional ethical rules (for example, client confidentiality, conflicts of interest, duties to the court and advertising restrictions)*. A firm’s partners may be entrepreneurial and focused on “business” (non-law) issues; others may take the view it is not the role of lawyers to think about strategy, marketing or other “business” issues.

* In New South Wales, professional conduct and ethics rules are set out in the Legal Profession Uniform Law Australian Solicitors’ Conduct Rules 2015 and Legal Profession Uniform Legal Practice (Solicitors) Rules 2015 and similar rules apply in each jurisdiction in Australia.

Doraisamy (2015) identifies that legal practice naturally attracts people whose personalities are predisposed towards pessimism, perfectionism and competitiveness. Legal work involves:

- Close attention to details, thinking critically, skeptically and applying logic.

- Finding fault with others’ arguments, identifying risks and depicting worst-case scenarios.

- Applying precedent: studying past cases to make predictions about the future.

- Mostly individualised effort, rather than collaboration.

- Solving intellectual problems, with complex, interesting or unique cases preferred over the routine.

- High-pressure decisions where misjudgement can have far-reaching consequences.

The nature of legal work, and the personal attributes of lawyers, are reflected in descriptions, and criticisms, of law firm culture, and how law firms operate. Beaton and Kaschner (2016) note there is an “emphasis on technical perfection” inherent in the BigLaw business model and “scant regard for the relationship between resource allocation and risk”.

Competitive personalities may be to blame for the “long hours” culture of many law firms. Schiltz (1999) notes that long hours are the single most complained about aspect of legal practice and argues that it results from lawyers engaging in a competitive “game”, in which billing income is how the “score” is kept.

Simpson (2016) describes the legal profession as slow to innovate because it is bound by tradition, its privileged status and desire to maintain high fees and Mountain (2002) notes that law firms have more of a cultural resistance to new technologies than, for example, accountancy firms.

The culture prevalent in many law firms also has a darker side. Bowling (2015) summarises a literature that finds lawyers have higher rates of depression, anxiety, suicide and alcohol abuse than the general population.

Role of culture in explaining firm performance

A significant stream of literature has assessed how organisational culture plays a role in determining organisational performance or effectiveness. For example, Keller and Price (2011) define culture as one aspect of “organisational health” and show that companies with strong organisational health profiles display above median financial performance:

Schein (1984) observes that organisations face two kinds of problems: external adaptation and internal integration. For Denison et al (2004), firms with an effective culture are those that can resolve the contradictions caused by addressing both types of problem simultaneously, without relying on simple trade-offs.

Role of culture in adapting to change in the legal sector

Organisations must perform in the current environment, but also be able to respond to changes in their macro-environment. Hock et al (2016) review a literature that finds an organisation’s ability to change depends on its culture and establishes that a novelty-oriented organisational culture encourages innovativeness.

In the context of PSFs, Lowendahl et al (2001) describe how a firm’s resources are a combination of tangibles (such as finances or buildings) and intangibles (expertise, reputation, client loyalty, culture and management skills) that may be usefully applied to generate value for the firm and its stakeholders. Culture is therefore a part of a firm’s resource base, which is a component in how PSFs create value.

Conversely, culture can have a detrimental effect on a firm’s ability to adapt. Echoing the connection made by Schein (1984) between culture and problems of “external adaptation”, Christensen (1997) identifies that firms develop capabilities, organisational structures and cultures that are tailored to the distinctive requirements of their current value network. A firm’s success leaves it captive to the financial structure and organisational culture that is inherent in that value network. Culture therefore forms an important part of a firm’s “RPV (resources, processes and values) framework”, which is central to Christensen’s explanation of how firms can often fail to respond to “disruptive innovation”.

This literature review originally formed part of my MBA thesis on “Making law firms a great place to work: a case study on the role of a firm’s business model in developing a successful workplace culture”.

References

Beaton, G. and Kaschner, I. (2016) Remaking law firms: why and how. American Bar Association.

Cutler, S and Daigle, D. (2002) Using Business Methods in the Law: The Value of Teamwork among Lawyers. Thomas Jefferson Law Review 2002(25), 195-222

Deal, T. and Kennedy, A. (1982) Organization Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Organizational Life. Addison Wesley.

Doraisamy, J. (2015) The Wellness Doctrines for Law Students and Young Lawyers. Xoum Publishing.

Hock, M., Clauss T. and Schulz, E. (2016) The impact of organizational culture on a firm’s capability to innovate the business model. R&D Management 46(3), 433-450.

Hofstede G., (1981) Culture and Organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization 10(4), 15-41.

Hofstede, G., Neuien, B. Ohayv D.D. and Sanders, G. (1990) Measuring Organizational Cultures: A Qualitative and Quantitative Study Across Twenty Cases. Administrative Science Quarterly 35(2), 286-316.

Peters, T. and Waterman, R. (1982) In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best Run Companies. Harper & Row.

Schein, E. (1984) Coming to a New Awareness of Organizational Culture. Sloan Management Review 25(2), 3-16.

Schein, E. (2004) Organizational Culture and Leadership. Jossey-Bass.