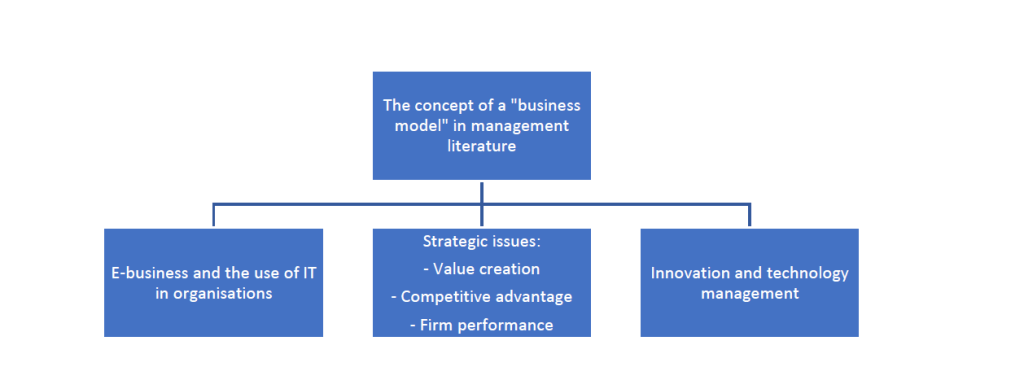

Although the focus of significant managerial and academic attention, a review of management journals by Zott et al (2011) found that the “business model” concept:

- had only recently emerged;

- was often studied without explicit definition of the concept; and

- was most frequently used in three streams of academic interest, or “silos”.

A differentiated and hard-to-imitate architecture for a firm’s business model can provide an important element of competitive advantage (Teece, 2010) and Zott et al (2011) identified that business models can play a central role in explaining firm performance.

Different definitions of the business model concept illustrate the connection between inputs (or resources) and outputs (value created or performance). For example, Osterwalder et al (2005) see business models as:

a conceptual tool that contains a set of elements and their relationships and allows expressing the business logic of a specific firm. It is a description of the value a company offers to one or several segments of customers and of the architecture of the firm […] to generate profitable and sustainable revenue streams.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. and Tucci C. (2005) Clarifying Business Models: Origins, Present, and Future of the Concept. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 16(1), 1-25.

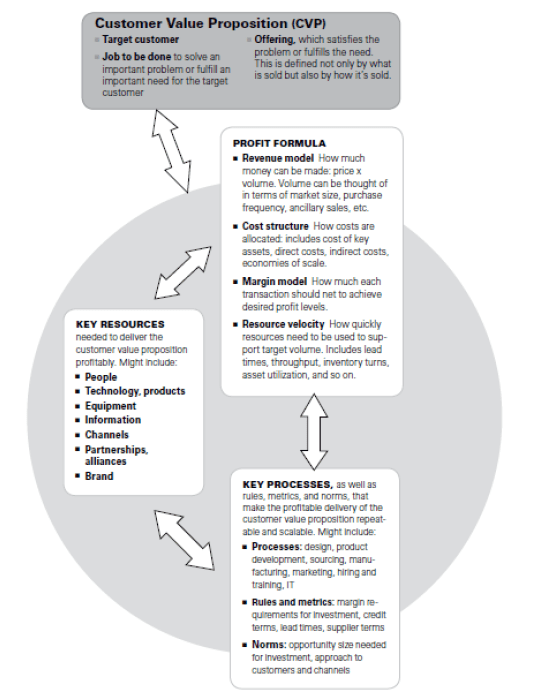

Similarly, Johnson et al (2008) see a business model as consisting of four interlocking elements that create and deliver value:

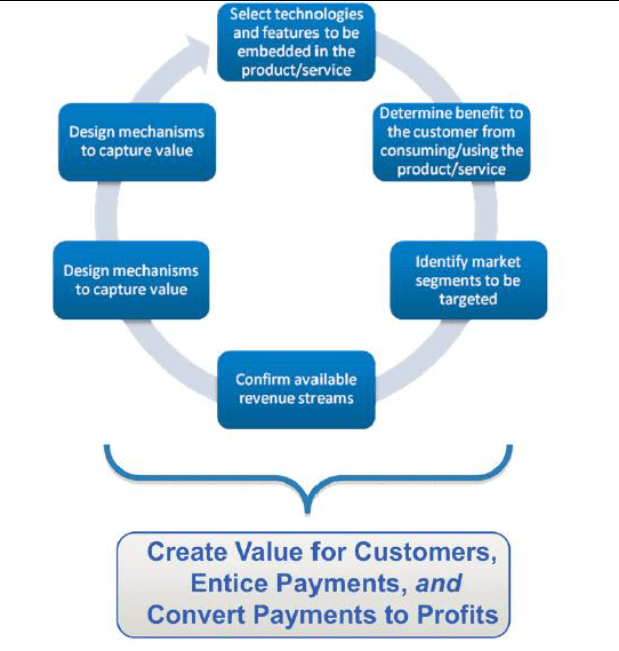

According to Teece (2010), a business model is the architecture that explains value creation, delivery and capture and is a means of defining how an enterprise can organise itself to deliver value to customers, entice payment for that value and converts the payment to profit:

Attributes of a traditional law firm business model

The Merriam Webster dictionary defines a law firm as “a group of lawyers who work together as a business”. The business comprises providing legal services to their clients for a fee. Law firms can be categorised as Professional Services Firms (PSFs) (von Nordenflycht, 2010), usually characterised by a professionalised workforce, high knowledge intensity and low capital intensity.

Law firms are distinguishable from lawyers that work by themselves (“solo practitioners”). A law firm can range in size from just two, or a few, partners (“boutique” practices) up to international firms that employ many hundreds of lawyers (termed “BigLaw” firms). Firms might focus on specialist areas of legal practice, or adopt a “full service offering”, where the firm is able to service any legal need a client may have.

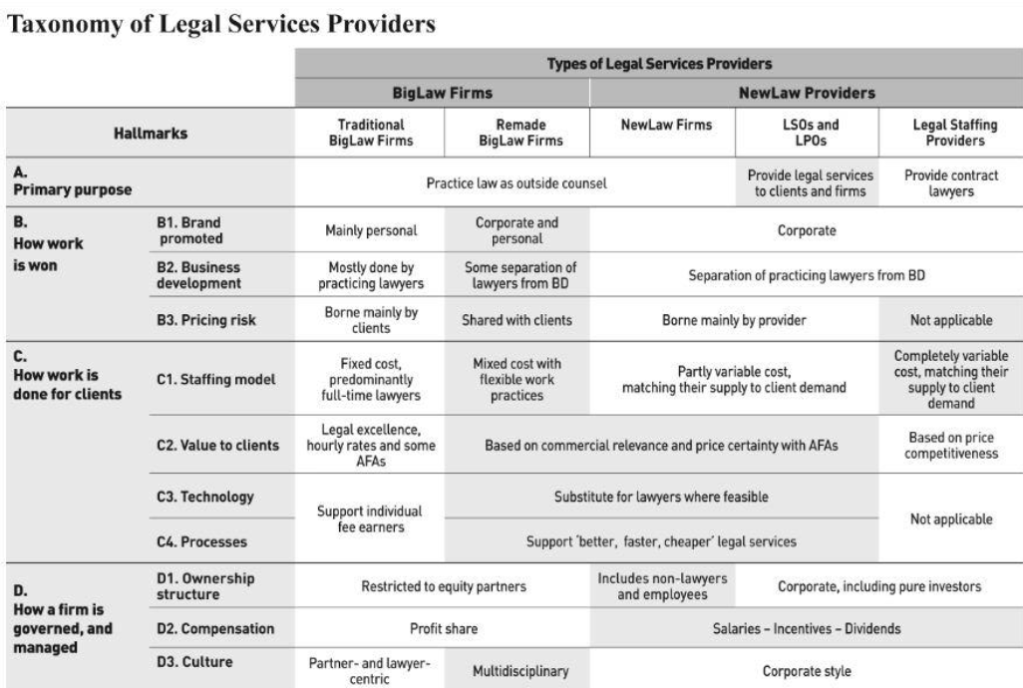

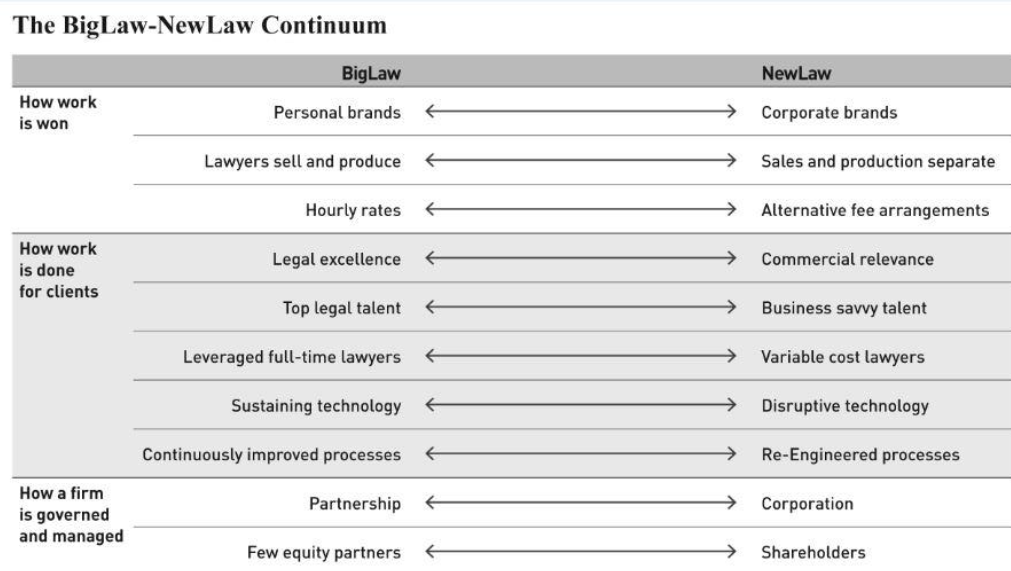

Focusing on law firm business models, Beaton and Kaschner (2016) differentiate traditional BigLaw business models from “NewLaw firms” to create a taxonomy of legal service providers (Figure 6) and a “BigLaw-NewLaw Continuum” (Figure 7), based on:

- how work is won;

- how work is done; and

- how the entity is governed.

Nature of the activities performed by law firms

One theme in business model literature is how firms organise their resources to perform activities that create value. Porter’s value chain theory (1985) is often applied in analysing a firm’s activities. However, Stabell and Fjeldstad (1998) argue that the value chain framework is less suitable for analysis of activities in service industries. They argue there are three generic configurations: value chains, value networks and value shops. Law firms are “value shops”: they create value by applying “intensive technology” (lawyers and their human expert legal problem-solving abilities) and by “mobilizing resources and activities to resolve a particular customer problem”. Christensen and Johnson (2009) describes this value creation logic as a “solution-shop business model”. A customer problem comprises being in one state (the client has a legal problem) and desiring to be in another state (the problem resolved). Key activities performed during this process by a value shop include problem-finding, problem-solving, choice of solution, execution of the solution, control and evaluation.

Another perspective on law firm activity is that some clients value being able to externalise the potential costs flowing from legal risks. The client seeks a law firm’s opinion that it is “safe” to proceed with an action, knowing that if issues have been missed or the opinion is negligently given, the client has recourse against the law firm and its professional indemnity insurer.

Nature of legal services offered

Law firms offer a vast range of legal services. In the commercial law firm sector, firms advise on corporate transactions, restructuring, tax, insolvency, antitrust, disputes, intellectual property and so on. A firm may segment its service offering by the type of law involved, or by adopting an industry or client-type orientation (for example, franchisors, the banking and finance sector or technology clients), or a combination of both.

Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) propose a “business model canvas” which includes consideration of “customer segments”. It is arguable that the types of legal service a firm chooses to offer is an issue of strategy, not business model design. For example, the business model taxonomy proposed by Beaton and Kaschner (2016) focuses on how work is won and done, not what work is undertaken.

However, understanding the types of legal services offered is relevant to examination of a firm’s business model because:

- the same segmentation may be adopted internally (for structuring departments and allocating resources within the firm); and

- it is relevant to the types of resources that a firm needs to build and how it organises those resources.

Legal services as credence goods

Legal services are a classic example of “credence goods”. Wolinsky (1993, 1995) defines these as “goods and services whose sellers are also the experts who determine the customers’ needs” and identifies that credence goods commonly have the following attributes:

- customers cannot determine the extent of service that is needed;

- customers cannot assess the quality of the service that was performed; and

- incentives for opportunistic behaviour by sellers.

In a similar context (management consultancy services), Christensen et al. (2013) identify it is difficult for clients to judge the consultant’s performance, because the very reason the firm is hired is for the specialised knowledge and capability that the client lacks.

The concept of “information asymmetry” has important consequences for law firm business models. Firstly, it explains the value that a law firm offers to its client (the lawyer is a professional and has knowledge that the client thinks it needs). Secondly, it creates incentives for lawyers, as sellers of legal services, to engage in opportunistic behaviour (Wolinsky, 1995), creating the need for regulatory bodies and codes of legal professional ethics, to protect otherwise vulnerable clients. Thirdly, it may have a role in explaining aspects of the traditional law firm business model. For clients who are selecting a firm to provide services, a firm’s reputation acts as a cue, or proxy, as to its quality (Day and Barksdale, 1992). Ribstein (2010) argues that law firms help clients overcome information asymmetry “by monitoring and screening potentially untrustworthy lawyers”. A firm has long-term reputational capital which its members seek to protect. Distinct from the legal work performed, law firms therefore offer value to clients by providing this “reputational bonding” function. Ribstein argues that reputational bonding has a role in explaining the prevalence of partnership governance structures and approaches to compensation and promotion decisions.

Degree of standardisation

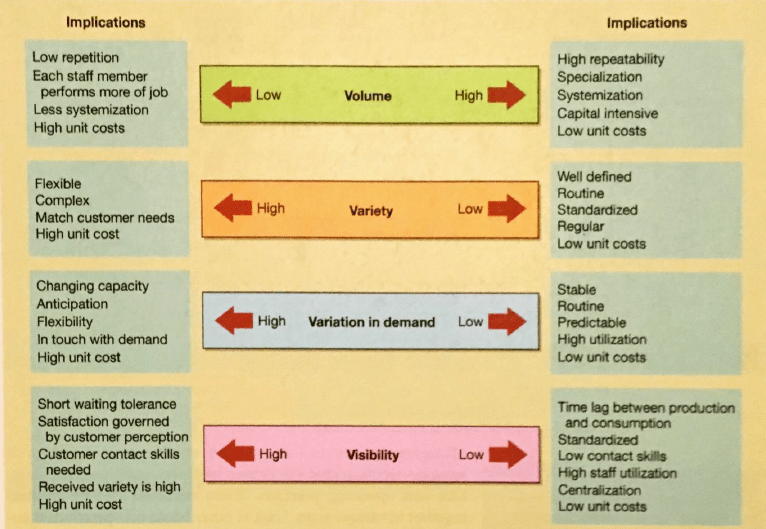

Legal services can be categorised by reference to the underlying processes involved in their delivery. The way processes are managed is influenced by the “four Vs of processes”: volume, variety, variation and visibility (Slack et al. 2009):

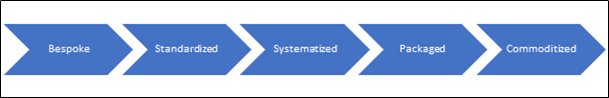

Stabell and Fjeldstad (1998) note that value shops are configured to deal with unique cases (low volume, high variety, high variation in demand and high visibility). Although many cases handled by the firm may be routine, a specialist professional must always remain involved, to identify those cases which have unique factors that require the professional to bring their greater experience to bear. Susskind (2013), however, notes that “much less legal work requires bespoke treatment than many lawyers would have their clients believe”. He describes an “evolution of legal service” comprising five stages:

Partnership structure

Law firms are traditionally structured as partnerships, although other forms of ownership structure are now also more common, including privately incorporated or publicly listed enterprises. One explanation for the prevalence of partnership structures is that historically (in Australia and in the UK), and still (in the USA), ethical rules and professional regulations have prohibited ownership of law firms by non-lawyers. Law firms commonly operated as partnerships, with the partners performing the functions of fee-earning, management and ownership. Ribstein (2010) argues that partnership structures arose because they offered the optimum means for law firms to ensure proper governance, and maintain their reputation for quality service, by aligning incentives through salary, promotion and liability. However, he notes that changes in the firms’ macro-environment have unleashed pressures on BigLaw firms’ business models, including their traditional partnership structure, which now require “fundamental restructuring”.

Beaton and Kaschner (2016) observe another possible disadvantage of a partnership structure, linking traditional firm ownership and capital structures (which return profits each year to partners) with resistance to change and innovation, where more access to external capital may be required.

Human resource strategies

A key attribute of a “value shop” configuration is that firms are labour intensive, with domain experts forming “the core and very frequently the largest component of the workforce” (Stabell and Fjeldstad, 1998). Von Nordenflycht (2010) observes there are “cat-herding” managerial challenges in retaining and directing an intellectually skilled workforce:

- skilled employees are in a strong bargaining position relative to the firm because their skills are scarce and transferable; and

- skilled employees favour autonomy and may have a distaste for direction, supervision or formal organisational processes, making it harder to direct them to do things they don’t want to do and authority more problematic.

Law firm partners (owners) only have a finite number of their own hours to sell. Law firms achieve growth and profitability by leveraging the experience of senior lawyers to supervise work undertaken by junior associates, whose work is also billed to a client. Traditional law firms therefore tend towards a “pyramid” organisational structure. Beaton and Kaschner (2016) note “leverage” (the number of lawyers per owner-partner) is a key component of Maister’s profitability formula which has been highly influential in shaping law firm strategy (see Maister, D. (1993) Managing the Professional Services Firm. Simon & Schuster). Ribstein (2010) describes a temptation under the traditional law firm model to increase short-term revenue through increased leverage (hiring more juniors), but that this reduces the partner’s ability to supervise, risking the firm’s long-term reputation for quality.

Ribstein also describes how law firms incentivise junior lawyers and determine who will be promoted and invited to become a partner (and owner) of the firm. The quality and value of the partnership is maintained because junior lawyers are put through a “tournament” which promotes those that contribute to building the firm (by having the “right” cultural values and levels of productivity, measured in hours billed and volume of client work won for the firm). Henderson (2008) describes how law firms have converged on this staffing strategy, referred to as “up-or-out” or the “Cravath system”*, describing it as:

Hire the best graduates from the best law schools; provide them with the best training; and at the end of a six to ten-year apprenticeship, promote the best associates to partner.

Henderson (2008)

*The “Cravath system”: A set of law firm management principles adopted by the US firm Cravath, Swaine & Moore (as described in Swaine, R. (1948) The Cravath Firm and Its Predecessors 1819-1948. Ad Press, Ltd).

Hourly billing

Traditional law firms usually use time-based hourly billing methods. This method became popular among US law firms in the 1960s and was subsequently adopted in other jurisdictions, including the UK and Australia. Lawyers record time spent on individual client matters, with the bill reflecting time multiplied by the lawyer’s hourly rate. There is an inherent tension in time-based billing. Increased law firm revenue requires more time to be charged to the client. This discourages both efficiency in carrying out work and investment in finding new, more productive ways, to work. Recording time emphasises the opportunity cost of time spent on “non-billable” matters, even if those activities may represent a valuable investment. Hours spent developing improved ways of working cannot be billed to clients.

Time-recording and time-based billing also have a pervasive effect on law firm processes and values. For a law firm’s managers, time recording is a convenient tool for measuring, monitoring and comparing associate lawyers’ performance. Fortney (2000) notes that billing information is used by firms to set billing expectations or targets (whether formalised, or established informally). Performance reviews and compensation or promotion decisions are usually tied to billing performance.

In an increasingly competitive market, where firms find it difficult to raise rates, Schiltz (1999) notes that the only option for firms is to bill more hours. However, the combination of accounting for time spent with high billing targets are a major source of stress for law firm employees. In a survey of Australian lawyers, Bergin and Jimmieson (2014) found that lawyers with high billing targets experienced greater anxiety, more stress, more job dissatisfaction and less work/life balance.

Criticism of billable hours is not new. Even 20 years ago, Jones and Glover (1998) described hourly billing as “under attack from market forces, technological advances, and most importantly, clients” and argued for alternate billing methods that benefit both the lawyer and the client. The Law Society of New South Wales (2017) highlights the value of time recording for understanding labour input costs, but identifies clear client appetite for billing alternatives that reflect the value created, not just time incurred. However, Beaton and Kaschner (2016) argue that most law firms have only responded to this client appetite by discounting their hourly rates, rather than moving away from time-based practices.

This literature review originally formed part of my MBA thesis on “Making law firms a great place to work: a case study on the role of a firm’s business model in developing a successful workplace culture”.

This research used a case study approach to examine an Australian multi-disciplinary firm that had won awards as a “Great Place to Work” and for its innovative culture.

The second part of the literature review component looked at Law Firm Workplace Culture – see here.

References

Beaton, G. and Kaschner, I. (2016) Remaking law firms: why and how. American Bar Association.

Bergin, A. and Jimmieson, N. (2014) Australian Lawyer Well-being: Workplace Demands, Resources and the Impact of Time-billing Targets. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 21(3), 427-441.

Christensen, C. and Johnson, M. (2009) What Are Business Models, and How Are They Built? Harvard Business School Module Note 610-019.

Christensen, C., Wang D. and van Bever, D. (2013) Consulting on the cusp of disruption. Harvard Business Review 91(10), 106-114.

Day, E. and Barksdale, H. (1992) How firms select professional services. Industrial Marketing Management (21)2, 85-91.

Fortney, S. (2000) Soul for Sale: An Empirical Study of Associate Satisfaction, Law Firm Culture and the Effects of Billable Hour Requirements. University of Missouri-Kansas City Law Review 69(2), 239-309.

Henderson, W. (2008) Are We Selling Results or Resumes? The Underexplored Linkage Between Human Resource Strategies and Firm Specific Capital. Indiana Legal Studies Research Paper No. 105.

Johnson, M., Christensen, C. and Kagermann, H. (2008) Reinventing Your Business Model. Harvard Business Review 86(12), 50-59.

Jones, S. and Glover, M. (1998) The Attack on Traditional Billing Practices. University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Journal 1998(20), 293-311.

Law Society of New South Wales (2017) Report of the Future of Law and Innovation in the Profession Commission of Inquiry.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. and Tucci C. (2005) Clarifying Business Models: Origins, Present, and Future of the Concept. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 16(1), 1-25.

Osterwalder, A. and Pigneur, Y. (2010) Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. Wiley.

Porter, M. (1985) The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Free Press.

Ribstein, L. (2010) The Death of Big Law. Wisconsin Law Review 2010(3), 749-815.

Schiltz, P. (1999) On Being a Happy, Healthy, and Ethical Member of an Unhappy, Unhealthy, and Unethical Profession. Vanderbilt Law Review 52(4), 871-951.

Slack, N., Brandon-Jones, A., Johston, R. and Betts, A. (2009) Operations and process management: principles and practice for strategic impact. Pearson Education Limited.

Stabell, C. and Fjeldstad, O. (1998) Configuring Value for Competitive Advantage: On Chains, Shops, and Networks. Strategic Management Journal 19(5), 413-437.

Susskind, R. (2013) Tomorrow’s Lawyers: An Introduction to Your Future. Oxford University Press.

Teece, D. (2010) Business Models, Business Strategy and Innovation. Long Range Planning 43(2010), 172-194.

Von Nordenflycht (2010) What is a Professional Service Firm? Towards a Theory and Taxonomy of Knowledge Intensive Firms Academy of Management Review, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 155-174, Jan. 2010.

Wolinsky, A. (1993) Competition in a Market for Informed Experts’ Services. The RAND Journal of Economics 24(3), 380-398.

Wolisnsky, A. (1995) Competition in Markets for Credence Goods. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 151(1), 117-131.

Zott, C., Amit, R. and Massa, L. (2011) The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. Journal of Management 37(4), 1019-1042.